By Marylene Delbourg-Delphis @mddelphis

Note: This book will be published in French by Diateino in January 2011. As a reminder, Diateino is also the French publisher of Seth Godin’s and Guy Kawasaki’s most recent books. To read my French version of this preface, please go to the Diateino blog.

***

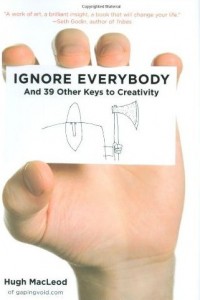

I’m a cartoonist – This is how Hugh MacLeod introduces himself on his blog, www.gapingvoid.com.

In France, the word “cartoonist” generally refers to the creators of American animated cartoons. In English, the term applies to any person who draws cartoons in a variety of formats — such as editorial cartoons, comic strips, comic books, or animation. The word comes from the Italian “cartone” that started to designate preliminary drawings and sketches for paintings, stained glass windows, and tapestries early in the sixteenth century. Even though the Webster reports that the first known use of “cartoon” in English dates back to 1671, Punch Magazine is the publication that gave the word its modern meaning in 1843 by labeling one of its illustrations, “Cartoon, No.1: Substance and Shadow,” a satirical drawing where caricaturist John Leech (1817-1864) was deriding the preliminary drawings of the paintings that were to decorate the Houses of Parliament under reconstruction because of the 1834 fire. From then on, “cartoons” started to brand humorous drawings that often had social and political undertones. During the same period, France also has its “cartoonists”, of course, such as J.J. Grandville, Honoré Daumier, or Charles Philipon; however the French press never went into a similar intensive marketing of cartoons as its Anglo-Saxon counterpart did. As indicated by Jean-Paul Gabilliet, one of the rare French specialists of American cartoons, “the democratic mythologizing of press illustrations in France only happened in the nineteenth century and faded after WWI, with images being treated as a mere additive to writings.” Nonetheless, Gabilliet does not fail to mention contemporary notable exceptions, such as Cabu or Pétillon.

In France, the word “cartoonist” generally refers to the creators of American animated cartoons. In English, the term applies to any person who draws cartoons in a variety of formats — such as editorial cartoons, comic strips, comic books, or animation. The word comes from the Italian “cartone” that started to designate preliminary drawings and sketches for paintings, stained glass windows, and tapestries early in the sixteenth century. Even though the Webster reports that the first known use of “cartoon” in English dates back to 1671, Punch Magazine is the publication that gave the word its modern meaning in 1843 by labeling one of its illustrations, “Cartoon, No.1: Substance and Shadow,” a satirical drawing where caricaturist John Leech (1817-1864) was deriding the preliminary drawings of the paintings that were to decorate the Houses of Parliament under reconstruction because of the 1834 fire. From then on, “cartoons” started to brand humorous drawings that often had social and political undertones. During the same period, France also has its “cartoonists”, of course, such as J.J. Grandville, Honoré Daumier, or Charles Philipon; however the French press never went into a similar intensive marketing of cartoons as its Anglo-Saxon counterpart did. As indicated by Jean-Paul Gabilliet, one of the rare French specialists of American cartoons, “the democratic mythologizing of press illustrations in France only happened in the nineteenth century and faded after WWI, with images being treated as a mere additive to writings.” Nonetheless, Gabilliet does not fail to mention contemporary notable exceptions, such as Cabu or Pétillon.

A cartoonist, a writer, an entrepreneur, whatever! A creative mind…

Hugh MacLeod is a cartoonist in the pure sense of the Anglo-Saxon tradition. He is a writer: this is clear from his book’s climb onto the Wall Street Journal’s Best Sellers list. He is an entrepreneur: in 2006 he became the CEO of Stormhoek USA that markets South-African wines in the United States. He worked in advertising intermittently until 2004, starting right after college, needing a job to pay for his bills. All such activities anchor him in what he calls “the real world,” as he deems living as an “artist” to be too unpredictable. Is this too much of a compromise when you are an artist? It’s a matter of vantage point. In fact, it’s by securing a revenue stream that MacLeod was able to do what he wanted to do as an artist – and ultimately without compromising. “The most important thing a creative person can learn professionally is where to draw the red line that separates what you are willing to do from what you are not. It is this red line that demarcates your sovereignty; that defines your own private creative domain.”

In this book, which reads like an autobiographic essay, Hugh MacLeod shares his experience and his perspective. Whether you are an artist or an entrepreneur, your personal obligation is to protect your freedom and your sovereignty: this is what will enable you to constantly more forward, pushing you to innovate as well as find the self-sufficiency that frees you from the tyranny of others — friends who see you a certain way, always the same over the years, or colleagues who box you in categories based on what is professionally convenient to them or on what fits with the stereotypes with which they comply. So, if you are an artist, don’t get trapped into the romantic clichés of the misunderstood genius ready to starve for the sake of Art; if you are an entrepreneur, keep away from buzzwords and sing in your own voice. Your goal is certainly to be recognized, but your chances of succeeding are higher if you accept solitude and beaver away. Yes, “Ignore everybody, but also “Just shut the hell up and get on with it. Time waits for no one.”

For MacLeod, success didn’t come overnight. He crafted it. It’s a success earned through work, patience, and his ability to leverage the platform of expression that the Web offers. MacLeod could have waited to be recognized through traditional means. Instead, he chose to create his luck. His free spirit made him choose self-publication in his own “magazine,” his blog. Hugh Macleod is a cartoonist, yes, but on his own terms, and on a ubiquitous tribune.

An artist…

Ignore Everybody contains two books in one. It’s a text, of course. But it’s also a collection of cartoons to be appreciated separately, that tell a slightly different story even as they illustrate the narrative. They display a whole different dynamics, capturing the precariousness of ideas, feelings and impressions, as well as the fleetingness of viewpoints: “One of the reasons I got into drawing cartoons on the back of business cards was that I could carry them around with me (…) So if I was walking down the street and I suddenly got hit with the itch to draw something, I could just nip over to the nearest park bench or coffee shop, pull out a blank card from my bag and get busy doing my thing. Seamless. Effortless. No fuss. I like it. Before, when I was doing larger works, every time I got an idea while walking down the street I’d have to quit what I was doing and schlep back to my studio while the inspiration was still buzzing around in my head. Nine times out of ten the inspired moment would have passed by the time I got back.”

These cartoons are a world in and of themselves. While the text of the book sometimes gives the impression that words thwart the communication of the message, the vignettes express the moment with vividness and perceptiveness, instantly revealing how MacLeod sees the world around him, be it personal or professional, what he likes as well as what he detests, humorously or ironically, yet almost always with an iconoclast and libertarian resonance. While the book compulsively hammers how urgent it is to resurrect in oneself personal leadership and creative energy free from constraints and conventions, the drawings accurately reflect that impulse, as does the laconic style of the comments that accompany them. MacLeod’s drawings have something of a Lettrist Hypergraphy manner à la Isidore Isou and a situationist energy à la Guy Debord. The cartoons of Ignore Everybody, as well as some if his drawings for a number of books, such as Seth Godin’s Linchpin, Nilofer Merchant’s The New How, or Barrie Hopson’s and Katie Ledger’s And What Do You Do?: 10 Steps to Creating a Portfolio Career carry the same clear message: Get away from what Guy Debord called “The Society of the Spectacle”, take charge of your own destiny, be constructive and innovate: “The only people who can change the world are people who want to. And not everybody does.”

… Or follow a great tradition by making it yours and enriching it with your own idioms, as is the case for MacLeod. He calls himself a Texan, but his father is Scottish, and he has spent part of his life in Great Britain. As a matter of fact, there is something quite European about his style. At times, you will think of Paul Klee’s pencil strokes, of entanglements in the style of Hundertwasser, of postures à la Ronald Searle, or of proliferations like Sempé (for whom “nothing is simple” and “everything gets complicated”). At times, the metal-wire-like lines surmounted with a black ball, a while circle, or a spiral may remind you of the tension, attraction and repulsion effects of some of Alexander Calder’s mobiles. In all cases, though, you will still discover a very personal style and, on the minuscule area of a business card, the large space of the experiences and fancies of an artist, expressed with the insolence and the cynical benevolence of the best cartoonists in history.

4 responses so far ↓

1 English translation of my preface to the French version of Ignore … | Cartoon World // Sep 24, 2010 at 5:10 pm

[…] English translation of my preface to the French version of Ignore … Related postsZolin | CARTOON STUDIOInformation Library » Cartoon Picture History – Drawing And …Calling Artists for Drawing – Big Event! (Nationwide) | How To …Drawing cartoons and a community center « Later OnHow to hire a character illustrator | Mascot design and cartoon …Watch cartoon network after 80 children are studyi « shoesnwpmfoNIKE SPORTSWEAR @ ATRIUM (SO ME / MR CARTOON) – Newsflash …coded by nessus […]

2 Tweets that mention English translation of my preface to the French version of Ignore Everybody by Hugh MacLeod -- Topsy.com // Sep 24, 2010 at 9:17 pm

[…] This post was mentioned on Twitter by Hugh MacLeod and Bob Wan Kim, CEO, Bob Q. Kim, CEO. Bob Q. Kim, CEO said: RT @gapingvoid: @mddelphiso wrote a great intro to the French edition of my book: http://bit.ly/ayZlIr […]

3 Inside Hockey!: The Legends, Facts, and Feats that Made the Game | Team Sport Guide // Sep 27, 2010 at 11:24 am

[…] English translation of my preface to the French version of Ignore Everybody by Hugh MacLeod […]

4 David Everitt-Carlson // Jan 23, 2011 at 10:15 am

I’ve known Hugh for 22 years and this captures him perfectly.

http://wildwildeastdailies.blogspot.com/2008/02/into-gapingvoid.html

David

Leave a Comment